Everything we are as a society, from the health of the economy to the car-based suburban lifestyles we lead (and even the food we eat), is predicated on the availability of affordable fossil fuels. What happens when the costs of global warming, regional insecurity, the irreversible decline of biodiversity, and the degradation of public health are no longer acceptable? What happens when we run out of cheap fossil fuels?

The world as we know it is built on energy-dense fossil fuels. There are millions upon millions of years of sun energy packed into each drop of oil, each pebble of coal, and each wisp of natural gas. Unlocking the energy within these resources has been the foundation of growth and progress since the Industrial Era. Nuggets of coal fueling Dickensian industrial plants were already incalculably ancient before humanity ever discovered fire. Yet, as a nation, we burn through these carbon fuels at rates exceeding comprehension to the tune of 7 billion barrels of petroleum, more than 1 billion tons of coal, and 6 billion cubic feet of natural gas – every single day. China consumes even more. The amount of energy nations across the globe must consume to support functioning economies and maintain modern lifestyles is mindboggling and, ultimately, unsustainable.

More Than Just Global Warming

Our entire economy is predicated on cheap, energy-dense carbon fuels. But as availability of these fuels decline and costs go up, our economic model can no longer sustain itself. It is unsustainable. The idea of constant economic growth is not only unrealistic, it has put us in an untenable economic situation living way beyond reasonable means. We live in a finite world. It’s common sense. There are only a finite number of resources, and only one Earth.

In a finite world, it makes sense that eventually extraction of fossil fuels will become too expensive. When we first started extracting fossil fuels, we started with what was easiest (and cheapest) to obtain. As we move to more difficult locations, such as deep-water rigs, or the Arctic, the costs increase. At some point, the costs will become untenable. Advocates of the energy status quo argue that our salvation may lay in the tar sands of Alberta or in shale oil. However, whereas it took about one barrel equivalent of oil to extract one hundred barrels of oil in Saudi Arabia in the 1950’s, the same energy input today only extracts between 1.5 to 4 barrels of oil from tar sands and shale. Nor are we likely todrill our way out of this bind. The United States only contains about 3 percent of the world’s crude reserves yet consumes nearly a quarter of global supply. By any measurement, the era of cheap energy is coming swiftly to a close and increasing domestic production will hardly slow the inevitable. Higher energy prices will translate into higher prices on everything, reducing demand, and ultimately stall the economy. Still, like textbook addicts, Americans cling to the hope of just a little bit more oil, a fix, whether through fracking or horizontal drilling, that will prolong our carbon high a few more years no matter the environmental costs.

Renewable Rehabilitation

Renewables offer unique long-term advantages. By their definition, they can be relied on to provide clean energy in perpetuity, as opposed to being quickly consumed. Every day enough sunlight falls on an acre of land in West Texas to produce the equivalent energy as 800 barrels of oil per year. Studies show that wind could theoretically power the nation. The energy sources are there, the problems lie in harnessing them. Detractors accuse renewables of being far too inefficient.

But in the grand scheme of things, fossil fuels are far less efficient. Think about it. Earth receives sunlight at a relatively constant rate. Yet, only a tiny fraction of that light is stored through photosynthesis, of which only a miniscule fraction is synthesised in plants located in appropriate environments for preservation, of which only a fraction coalesce into usable fossil fuels as we know them, of which only some is realistically extractable. Considering the immense amount of energy (in millions of solar energy) and time (in millions of years) necessary to produce a single gallon of gasoline, the price tag at the pump ought to be in the billions of dollars per gallon range. It takes 89 tons of ancient plant matter to produce a gallon of gasoline. Imagine trying to put that in your car’s tank. What we are doing is squandering hundreds of millions of years of our natural inheritance in the span of a mere century or two.

Catch 22

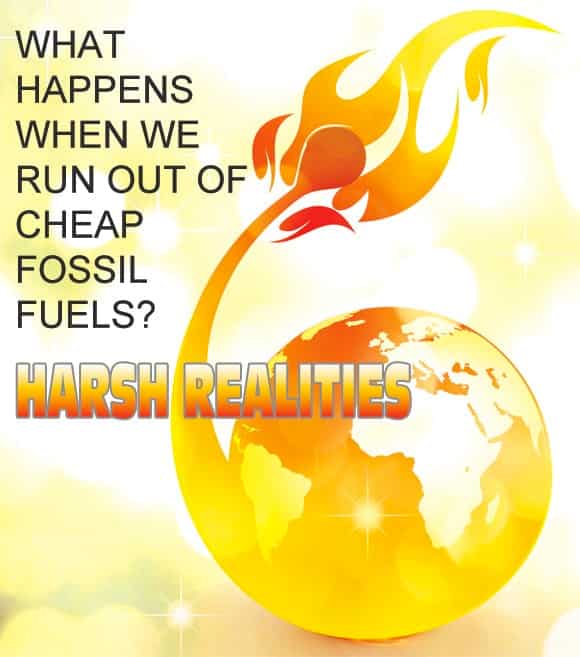

Continued reliance on fossil fuels carries some serious implications for the future. Sooner or later the transition from finite carbon fuels to renewables will occur by necessity. When that happens, brand new infrastructure will have to be built and distribution systems will need to be put in place. Here’s the catch: new infrastructure, technology, systems, and labor not only require much money, but much energy as well – precisely the one thing in short supply. It takes energy to get energy. What this tells us is that part of planning for the future must involve diverting funding, resources, and yes, energy, into the research and development of alternative sources right now.

Learning to Live in a Finite World

The goal of renewables is not to make life miserable. The goal of renewables is to ultimately displace rapidly disappearing, and environmentally destructive, fossil fuels as primary engines of economic growth. Clean tech continues to be our primary hope to combat global warming, pollution, and a stalling economy. Yet renewables currently only constitute about 3 percent of America’s energy mix. Wind and solar, both highly promising technologies, contributed less than 1 percent each. If the United States wants a smooth transition into the mid-twenty first century and beyond, the vigor in which we pursue the development of alternative sources of energy will determine not only the trajectory of global warming, but also our ability as a nation, and a superpower, to maintain high standards of living.

Live well. Think green. Build Native.

Global Warming

Global Warming Global Warming Global Warming Global Warming Global Warming Global Warming Global Warming

[…] recently in the national spotlight can testify, no longer can our nation’s politicians deny global warming and get away with it. Americans, and much of the world, can finally cross off step one of our […]

[…] all, all three methods of harvesting solar energy aren’t just about finding an alternative to fossil fuels, they’re also about saving […]

[…] are, it’s no surprise that other very real issues, such as climate change and anthropogenic global warming, tend to take a backseat in the face of an onslaught of other concerns that demand our immediate […]